A while back I wrote about how I was making art for In The Shadows. Since the release in October last year, I had some time off from designing visuals for the game so I thought it would be the perfect moment to document my process in more details. It will be a sort of reference for myself and for anyone interested in making a game with the same approach, visual style, or to add to it and make something better.

The art direction and the look of things is always closely related to how I do things, as a matter of fact, how I do things usually dictates it. I rarely make something without knowing how I can do lots of it easily, it’s a manufacturing mindset really. If I come up with things that I can't mass produce, I usually dismiss it. It's not that I will necessarily mass produce it, but figuring out the best way of doing something will help later on if or when I have to do it again. My workflow is usually the simplest, easy approach to solving a problem. My general approach is that having a small number of step to achieve something is not as important as the ability to automate it easily. I will favor multiple simple steps over complex operation, since simple steps even if numerous, are easy to automate later on.

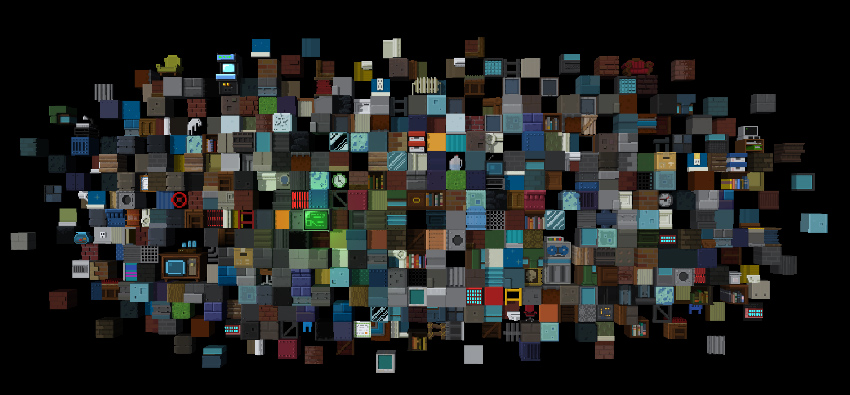

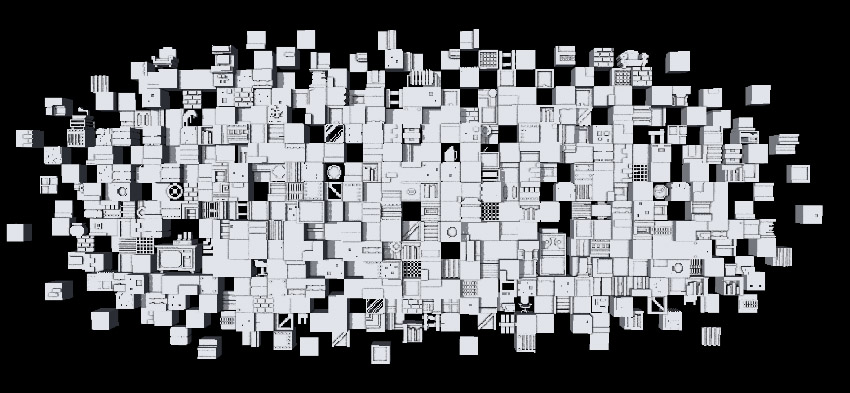

Enlarge / A glimpse of some of the tiles for In The Shadows. Since I had to make a lot of graphics I had to figure out a good workflow.

Of course if my priority is building assets fast, sometimes some other aspects may suffer. For example let's say a certain setup, like in my case the way I am building the voxels; They are made in a voxel editor then exported as 3D mesh. There is some optimization done on the mesh when exported but consider that I work with many many tiles and not one single big object. I end up with hundreds if not thousands of objects in a scene. A workflow decision based on making the art fast can make things heavier to calculate in real time conditions in this case, but for me optimization is often secondary and is dealt with later in production. I do think about it when dealing with stuff that I know will be heavy, but it is not a priority at that stage. Quality is also an issue, but the basic idea is making good looking art fast.

In my case, for the optimisation problem I had, I later merged all those tiles in the levels so that they would share a common shader and cut tremendously the amount of drawing calls for each frames. This was a solution that I knew I would have to implement later to make the game run smoother.

The pixel art look

From the beginning, I wanted In The Shadows to look very much like a 2D pixel art game. My original career background is from the 3D industry, making animated films, and I remember throughout the years seeing so many modern pixel art styled game and wondering why nobody was using 3D lighting techniques to light their scenes. There is a few examples of game that flirt with the idea but none really exploited it completely. What I really wanted to do was 2D pixel art, lit in 3D and casting real time shadows, but still appear like a genuine 2D pixel art game.

Enlarge / Left: In game orthographic view. Right: Perspective view in Unity. It's a bit sad that we never get to see the view on the right, but at the same time, it makes the view on the left possible, and I really don't see any other way I could have achieved the view on the left otherwise.

As you can see from the last picture, and might have already known, In The Shadows is in reality completely build in 3D using “voxels” to give depth to the scenes and enabling the possibility of real-time shadows casted from actual geometry. My workflow usually consists of making pixel art design of my objects (tiles) using PyxelEdit and later giving it depth in Qubicle, carving away and extruding, to create the 3D shape that I need. Objects Z positions is based on how I want them to cast shadows but I often have to cheat to cast more or less depending on the situation.

There was a lot of compromises I had to make while working on the game, related to the pixel art look, here are some of them, along with solutions and techniques I used to produce the art for In The Shadows;

Shadows resolution vs screen resolution

For the longest time I was making tests and rendering the scene with up-scaled pixels instead of just blowing up the rendered frame. This made the real time shadows very sharp as you can see on the next screenshots. After working with this setup for a while I got used to that look. I made some tests to see how the whole thing would look like if it was pixel perfect (including the shadows) and I ended up deciding to keep the high-resolution version since I liked that it gave “modern” feel to it. It also made some details look better in some situations.

The "high" resolution render on the left, as seen in the game. You can see the shadow on the right is very sharp and the light fall off on top left is very smooth. Compared to the up-scaled full screen image (rendered pixel for pixel then scaled up) the shadow on the right and the light fall off are both pixelated.

The difference might be subtle for most people or even unnoticeable for some, but I suppose if you want to stay closer to the pixel art look then the image on the right feel more genuine. For me though, I do preferred the one on the left. The fact that the render was also very big made it easier to control light ambient occlusion, which I use throughout the game. On the other hand, it also make the frame rate drop compared to a scaled up low resolution frame. Consider this; on a 1080 display, the pixels are in many cases 4x bigger than what they really are, so if I would just scale up the render it would be like rendering instead 480x270. Instead it's the camera frame that is scaled up, so the light occlusion, shadows, any effects on top of the image is calculated on a full frame 1080p, the art "pixels" are just bigger.

This is something you need to keep in mind when you are making a pixel art game in a 3D engine. Making it truly pixel for pixel, rendered at native size then scaled up will give you way, way better frame rate, especially if you have a lot of full screen camera effects on top of it.

Enlarge / Light ambient occlusion in game. You don't really notice it in game and I left the option to turn it off but it helps giving more depth to the voxels.

Pixel art style constraints

One of the constraints I gave myself while creating the art for the game was to keep working with tiles that have a multiple of 16x16 pixels. It made things easy to manage and gave it a consistent look, but I soon faced limitations and had to create often much bigger tiles. I still kept the 16x16 size as a default, and would use it as much as I can, but I didn't constraint to it if I needed to.

I think it's important to work with constraint though, when making any kind of art. It forces you to get creative to solve problems. When you have a blank canvas it's easy to get lost and not know what to do. If you constrain yourself, have clear limits about how you can do things, like pixel art in general where resolution is so important, you get very creative. When faced with something that you can't do with the constraints you set to yourself it opens the door to ideas you might not have had otherwise.

Animation

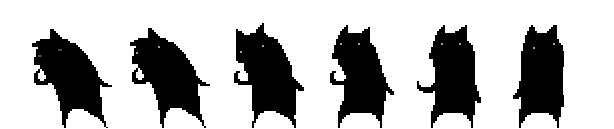

Most of the animation in the game is made frame by frame on 2D sprites. These sprites are rendered in the engine as flat billboards but I also use a normal map on the player sprite to give it more depth. It still enables me to cast shadows on the scene from these sprite and the added normal map on the player character helps a lot to blend the player in the scene. Shadows monsters are mostly black so it was important to keep a good silhouette to make the animation interesting. Keep in mind that this was my first time doing any kind of 2D animation, and looking back at it now I wish I put more time into it, but I'm still happy with the result in the game. I tried to keep a constant level of quality of animation throughout the game, even though the animation was rather simple.

Another compromise was made on the pixel snapping during translation of sprites and camera. In the game the player and camera move smoothly on a “subpixel” precision which make for a more natural movement and more precise control of the player. I decided to keep the movement like this after some testing with perfect snapping made the camera too jittery and the player too stiff. It would have made the 2D style more authentic, but I decided against it. Moving things on a "subpixel" basis does give more precision for the control of the player and camera. You should definitely try both approaches to see what feels better for your game.

Pixel snapping on the player movement: Subtle difference. If you look closely you can see the left leg of the player is in between two pixels on the ground.

Something that is worth trying is moving the player in subpixel space, but still pixel snapping the sprite. This way you would retain the position but visually it would look like a true pixel render. I am not sure how it would feel, or if it would be any different than regular pixel snapping.

Shadow creature look

The shadow creatures also have been through different iterations. One thing that I wanted to try was having the creatures actually made of casted shadows. This was very interesting visually but made things a lot harder to control in the game and much more confusing. It was also counterintuitive since to be able to cast a shadow the monsters need to be lit, and as the mechanics dictate, the monsters transforms into objects when they are in the light.

Some creatures lurking in the night

I could have made them transparent (the giant hand shadow in the game is semitransparent) but I also wanted them to "pop" and be easy to notice and decided to do the latter. As you can see in the previous image, even with the shadows completely black, it was still hard to see them sometimes. Also I did take advantage of the fact that you can't see them well in some situations as part of the gameplay, but it was really hard to balance, making "shadows" pop in a dark environment. The whole thing makes little sense, but in the end it still worked fine I think.

The hand. it's lurking and stalking. It is a piece of the puzzle that links the whole story together.

The hand animation, rotoscoping process

About those giant shadow hands. The hands animations you see in the game are actual captures of my hand that have been cleaned up and simplified. Removing in-between frames also helped make the animation more natural and feel less like pure rotoscoping. I had to "act" those movement and did a lot of takes before I got reference that I was satisfied with, nevertheless I had to splice some of those animation to make them work better together. It's all about the silhouette, when you work in high contrast, basically 1 bit, you need a very distinctive silhouette to understand what's going on.

A poor man rotoscopie capture setup. At some point I bought green sheets of cardboard paper to make things easier for myself.

For a time, the hand played a bigger role in the game, being a boss after each world, but even after removing those levels, it still kept its meaning throughout the story, with the ending revealing its true origin. The hand boss level changed the pacing too much, being too oriented on dexterity and timing, and mixing those with puzzle elements just didn't fit with the rest of the game.

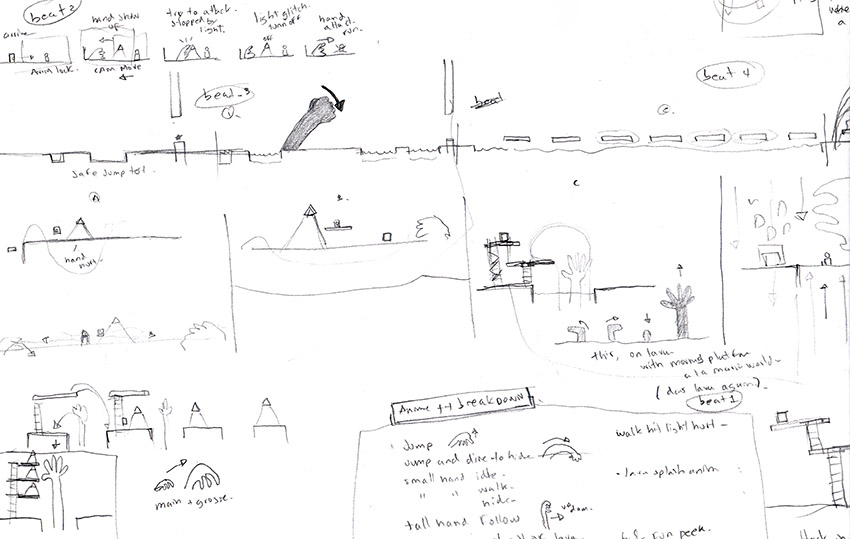

Examples of design ideas for the hand boss. I had a lot of ideas for it, but the first prototypes were just too different from the rest of the game, gameplay wise.

It's important to figure out how you want to create art for your game, and I believe it is a very good approach to make art based on knowledge you already have, instead of trying to achieve something grandiose that you have no idea how to do. Remember that your process and the speed at which you can create the art will have a huge impact on how long you will have to work on that project and ultimately not getting tired of working on the same thing for too long.